Take It Easy

Josef Pieper's Path to Culture & Enlightenment

I used to keep a personal sabbath. It wasn’t a religious thing. I simply stopped extending or accepting invitations for Sunday activities. I reserved the day, instead, for staying home and “doing nothing.”

I wonder if Josef Pieper would have approved.

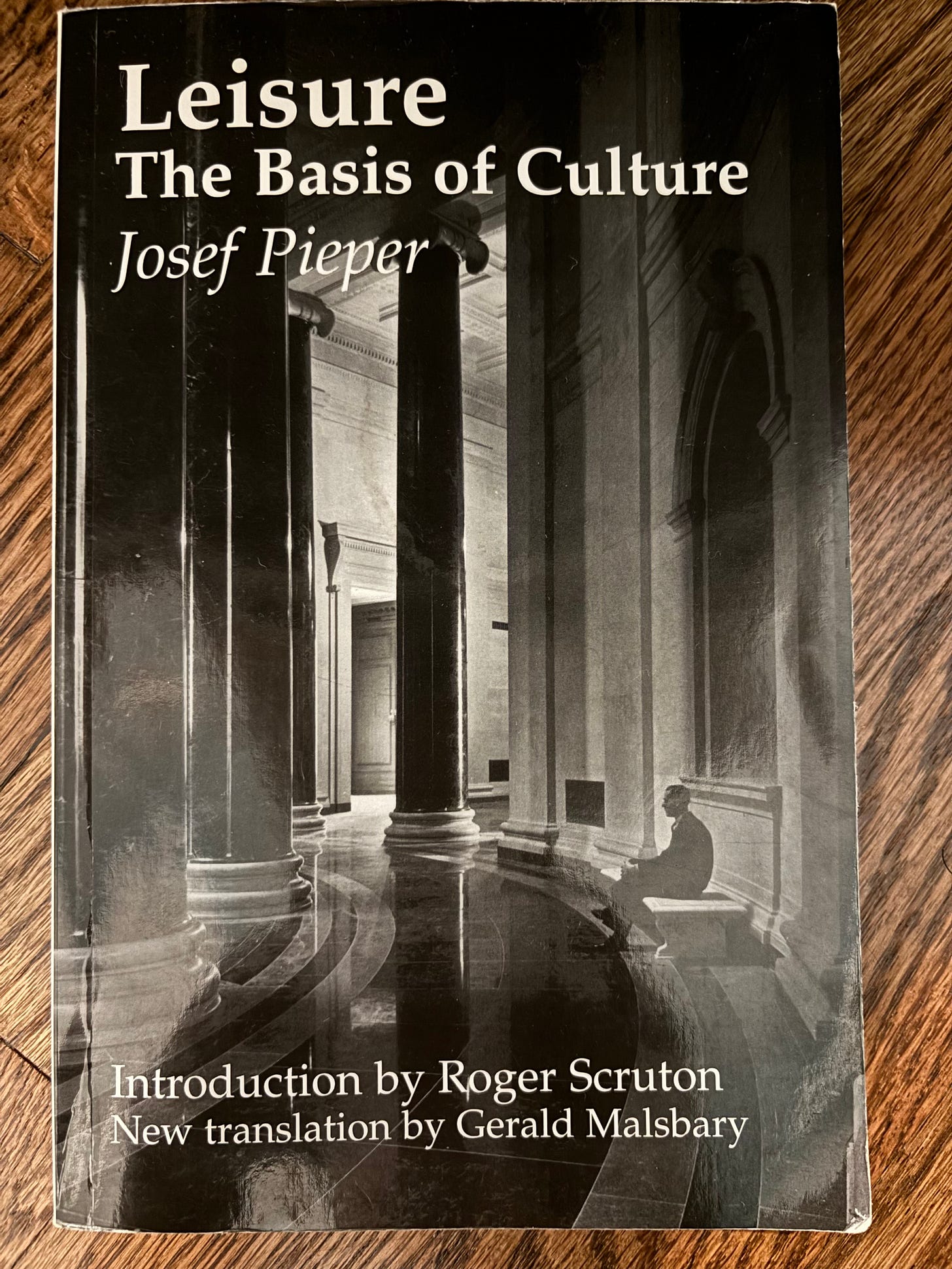

Pieper was a 20th century German philosopher whose book, Leisure, The Basis of Culture, I first read around that time. (My copy, published in 1998, was the 50th anniversary edition; the first printing happened in 1952.)

Pieper wrote from Germany in the wake of World War II when, by his account, his countrymen were feverishly “engaged in the rebuilding of a house” that was all but destroyed by the national socialists. A nation so focused on physical reconstruction, he worried, risked neglecting both the moral and intellectual reconstruction that were also needed. And that, he argued, could be achieved only by not working—through leisure.

It must have seemed a bold claim, given this was Germany, where a half century earlier Max Weber insisted “one lives for the sake of one’s work.” But Pieper reaches even farther back, quoting Socrates—“We are not-at-leisure in order to be at-leisure.”—to argue the primacy of inactivity.

Paradoxically, Pieper spills a lot of ink defining what “work” actually means. He references a whole bunch of other philosophers and thinkers to establish that it is not only physical labor, but also intellectual labor, and a bunch of other stuff besides—including the act of thinking using language. He also spends some time explaining what “at-leisure” means. Going to the Ravens game ain’t it. I suspect neither is sitting in a zendo emptying your mind in meditation.

Two of my earlier posts touched on what Voltaire and John Maynard Keynes thought about work. In his book Candide, Voltaire celebrates work not for its own sake, but for what it brings: freedom from boredom, vice, and poverty. Keynes, in The Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren, predicted the end of work as we know it (for subsistence) would trigger severe social distress: Who are we if we do not have work to occupy us?

Today, Artificial Intelligence and dramatic federal policies may have us on the brink of real widespread worklessness. Like me, you have probably read a bunch of pundit predictions and prescriptions on the topic. I have yet to come across any that advance Pieper’s vision.

His prescription for happy worklessness is rooted in religion—but not necessarily the overt or doctrinaire kind. Pieper (who was Catholic) seems to be content to have us sitting about, witnessing the world and feeling reverent or grateful. To be honest, his text never makes clear how this leads to culture—arts, music, etc. But it does open the door to an appealing kind of protean mystery that seems alien to single-minded pursuit of productivity or utilitarianism.

I experienced a share of gratitude and reverence during my idle Brooklyn Sundays. I suspect, though, that should widespread worklessness come to pass, the result will not be a bounty of reverence and gratitude.

Equally unlikely is the prospect that less work will create space for more robust or nuanced pursuit of distinctly human activities—like creating art and music, cultivating judgment, or deepening our interpersonal relations.

I hope I am wrong.

How about we check in again in another 50 years?

P.S. An additional paradox of this essay is that I did not find Josef Pieper an easy read. Following his reasoning was pretty challenging at times, and I frequently had to review some passages more than once. For example, he is prone to making an assertion, restating it differently—perhaps attributing the alternative to another thinker, and then recapitulating it yet again. This would be all well and good if the result were greater clarity. Too often, however, I experienced the outcome as additional, layered complexity (hence the need to re-read).

Since my work has been in the arts, does that mean on Sundays I should not sing? Something I’m pondering.

Fascinating!